Does ChatGPT Really Use Language Like You Do? The Answer Might Surprise You (Part V)

What the similarities/differences between LLM and human linguistic capabilities suggest about human-like understanding, embodiment, and fire

This post concludes this five-part series I’ve so sincerely enjoyed writing on LLM and human language capabilities.

Today, I’m going to review the similarities and differences discussed in previous posts to interpret what they may mean about the nature of intelligence, language, and human life.

Details, Details… Let’s Piece It Together (Clause by Clause)

First, I will summarize the past posts’ findings in this chart:

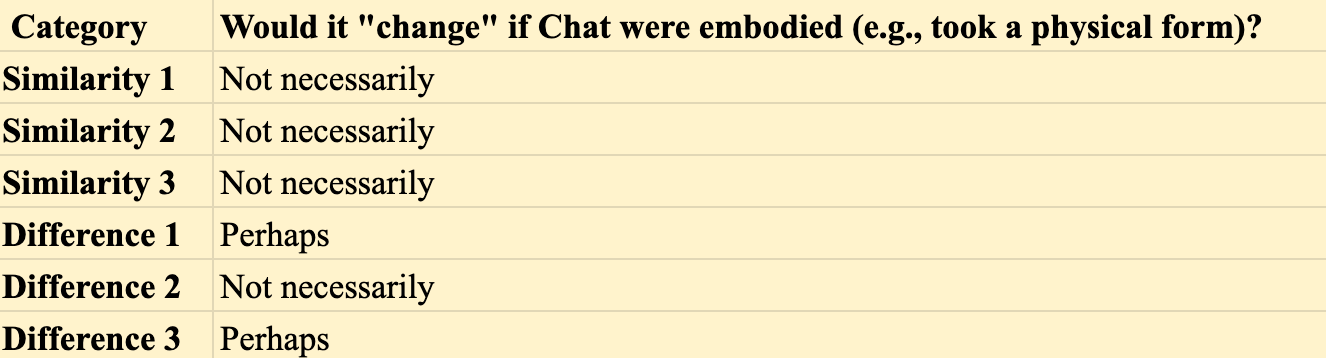

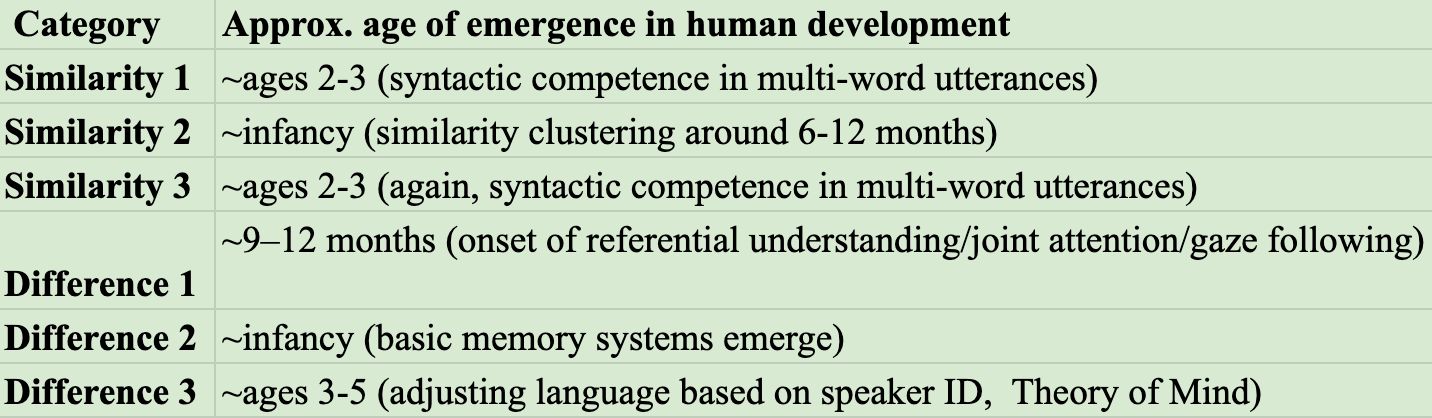

I hoped to contrast the similarities and differences across a few criteria:

Do the similarities/differences center more on language production or processing?

Do the similarities/differences involve certain kinds of knowledge in particular?

Would embodiment — e.g., the LLM taking on a physical form — reduce some of the differences?

When do the relevant capacities emerge in human development?

Processing or Production?

I began by looking for any clear patterns in whether the similarities/differences primarily pertain to language production or processing:

As you can see, similarities center on processing and production, while the differences more exclusively involve processing.

To me, that suggests that:

LLMs can approximate surface-level language competence, especially in production

However, LLMs diverge from humans sharply w.r.t. deeper processing involving understanding and context sensitivity…

So processing is where the biggest gap lies, imo

Further, that humans integrate syntax, memory, social awareness, and referential understanding into our language processing suggests human language processing is enmeshed with other forms of our sensorimotor/social intelligence.

What’s on the “Knowledge” Menu? Syntax, Semantics, Social Stuff

I then wanted to understand patterns in the type of knowledge being chiefly accessed by each similarity/difference:

My takeaways:

Syntactic knowledge appears prominently in similarities,

Pragmatic and social knowledge (e.g., referential understanding, sensitivity to speaker identity) appear only in differences.

So, in other words, Chat has more ease replicating human syntax than picking up on contextual or social nuances (which, intuitively, comes as no surprise!).

From Words to Worlds: Is a Body the Missing Link?

Relatedly, I was wondering if embodiment (e.g., direct sensorimotor experience and perceptual interaction with the physical world) would help bridge the gap between LLMs and human linguistic capabilities — especially where differences remain:

For all three similarities, embodiment is not necessary for the relevant capabilities to emerge. And why, you may ask?

Syntactic competence clearly can be learned from text alone (without grounded experience)…

… which supports the idea that surface-level linguistic structure can be modeled without a body.

But where differences arise, embodiment might help; if an LLM had access to sensory input and grounded social interaction, I hypothesize it may shift closer to human-like pragmatic processing.

However, the way that LLMs store knowledge in parameters (versus how humans use exemplar-based memory) is a product of architectural design and wouldn’t automatically change with embodiment per se.

The centrality of embodiment to referential understanding (and to human language processing more generally) underscores my intuition that LLMs will not “know” what they’re saying until they take on an embodied form — and develop some type of intent.

(Both of which children have, and animals too, for that matter).

These two features are necessary but not sufficient conditions for referential understanding, I theorize.

When Do Humans Develop These Capacities?

Finally, I wanted to see when the relevant capacities emerge in children:

There was not as obvious a pattern here as I expected. So, ix-nay on the theory that “LLMs emulate cognitive linguistic qualities that emerge earlier in childhood, whereas they have more difficulty with capacities that surface later in human life.”

While some differences between LLM and human language correspond to later-emerging abilities like Theory of Mind, other pertinent abilities that signal the start of referential understanding come into being quite early.

That alone suggests that human age of onset is not the decisive factor for determining whether a linguistic capacity is replicable by LLMs.

It appears that what matters more is the nature of the capacity itself — specifically, whether it relies on usage-based pattern learning (which LLMs handle fantastically) or on contextual, social, and embodied grounding (in which we have the upper hand, literally and figuratively… for now).

How, Then, To Interpret The Similarities?

As mentioned in Part III in much more detail: convergent evolution seems like an apt analogy when reflecting on human/LLM linguistic similarities.

I argued that human-like linguistic behavior might emerge in biological and artificial systems from general-purpose learning mechanisms.

“Different architectures may well arrive at similar solutions when tasked with solving similar challenges — such as, in this case, tracking long-distance dependencies, segmenting continuous input into meaningful units, and resolving ambiguity — especially when operating under comparable constraints like highly variable and noisy language input, generally limited access to negative evidence, and finite processing/memory capacity.”

A Closing Thought on Form Versus Function

LLMs can, indeed, replicate the form of human language. However, the function of LLM linguistic capabilities arose from a separate “evolutionary” pressure: principally, commercial imperatives. (And I hesitate to use the e-word when describing inorganic systems).

For homo sapiens, on the other hand, language either stemmed from an internal need to structure our thoughts (per Chomsky), or from an external necessity to communicate and coordinate with others in our species.

So, LLMs convincingly mimic the contours of language, but their reason for use is born of a different flame — one less bound to the evolutionary currents that shape (and have shaped) humankind’s narrative arc.

And “Speaking” of Flames:

On Thursday, I had the great joy of walking at Johns Hopkins University’s spring commencement ceremony where Sal Khan’s address mentioned the relation between fire and “the ability to gather and share knowledge.”

(By my friends’ and my accounts, Khan’s speech was phenomenal — perfectly capturing the intellectual curiosity and purposefulness that I’ve come to associate with my alma mater, and for which I’m so grateful).

This Promethean lens — of fire as world-changer, a catalyst for extended daylight hours, richer social interactions, and increased linguistic exchange — strikes me as a fitting metaphor to close out this series.

If fire once enabled humans to speak to each other, perhaps LLMs do not (for now) represent the fire roaring back at us. Rather, they are a manifestation of our own attempt to speak to the fire — to interact with tools and systems we’ve built, ones that have now acquired our tongues with uncanny fluency, yet still falteringly grasp1 at what it means to understand shared experience and enduring threads of generational memory.

So here ends the series on the parallels and divergences between LLMs and human linguistic capabilities. As always, thank you for parsing through these concepts with me.

May the discourse keep burning, sparking new questions across disciplines and dimensions (and yes, I intend every pun — knowing fully well that you, dear human reader, understand the referents of each one).

The series could not have possibly been complete without a nod to Prehension, which links the hand to linguistic cognition — a topic I hope to revisit in future posts!

Fantastic series

I learned a lot from this, you are a wonderful guide to this (to me) unfamiliar world