Why "Kroger’s" But Not "Costco's"? Michigan Apostrophes and the Invisible Store Owner

The visit to East Lansing that inspired me to run a quick experiment and ask what a grocery store is

When I visited Michigan for the first time last year, I learned that it’s home to fiber optics, spellbinding parks, and some of the kindest people alive.

Among the many wonderful things associated with The Mitten State is the linguistic phenomenon of attaching a possessive -s suffix to stores: “I’m getting bread at Kroger’s.” “Wanna go with me to Meijer’s?”

I found that endlessly cool, because in my dialect of English, “I’m going to [the store]’s” is as unheard of as “I’m going to school’s” or “I’m going to my cousin’s house’s.”

True to form, I found myself happily and obsessively tumbling down a rabbit hole. Specifically, I wanted to know what the limits of this pattern were. Hear me out.

At first, I casually speculated that the possessive -s suffix is attached only to grocers. But does it just have to do with grocery stores? And even then, something taxonomically interesting comes up: what is a grocery store?

For example: what happens if 58% of a store’s sales come from groceries? Then can you still use the -s suffix? What if a store is known for its clothes, but sells a few apples in a corner?

I predicted there would be some threshold of food merchandise sales — maybe around 50% — after which an -s suffix could acceptably be attached to a vendor. So, you could say “Aldi’s” but not “Home Depot’s.”

But that’s not what I found; the adding of -s was rooted in something else entirely.

The plan? Conduct a very unscientific but undeniably fun experiment in regional dialects.

I asked my favorite Michigander (and honestly, person) in the world for grammaticality judgments about adding the -s suffix to a range of vendors. The results were, in a word, fascinating. Here’s what he said.

Test 1: Grocers

Off the bat: a double possessive does not seem acceptable under any circumstances. The respondent wouldn’t add another -s if a store already ended in -s (so, “Trader Joe’s’s” was a nay).

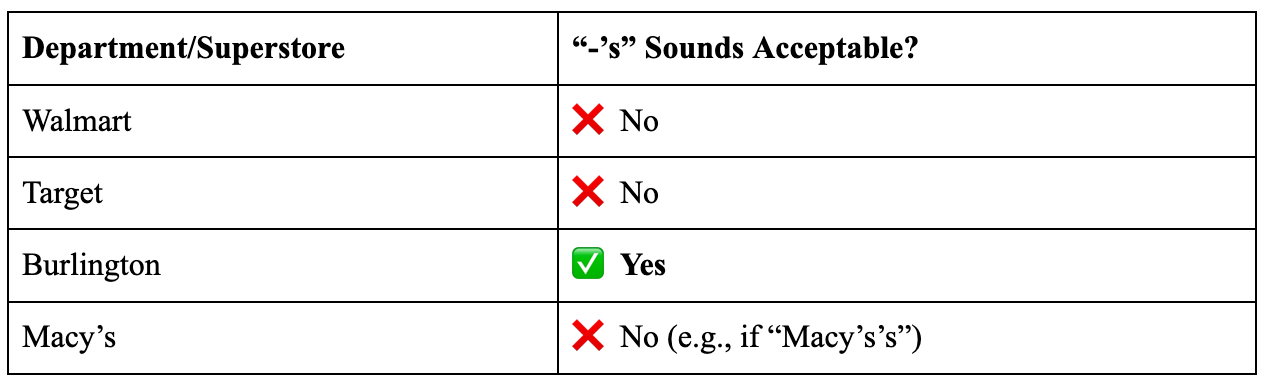

Test 2: Department/Super Stores

But what if a store sells groceries in addition to other products?

Cue the Target and Walmart results: selling food alone (even when it makes up the majority of sales!) does not confer -s acceptability.

Test 3: Fast Food Chains

Then, if the -s suffix is added to (some) grocers, can it be used with chains that sell food, too? Seems negative:

Test 4: Clothing Stores

Out of curiosity, what about places that sell no food, basically as a matter of principle?

Notably, Joseph A. Bank is a real human name!

Test 5: Online Vendors

Next subject: online vendors.

Test 6: Real Estate Services

I had my doubts about these sites, but they were worth a try:

Test 7: Sit-Down Restaurants

Finally, returning to the question of food sales. Again, serving meals is not the only prerequisite for -s appendage:

Takeaway: When Can You Add -S to a Store Name?

Well, I was wrong! As far as the respondent’s mental grammar was concerned, there didn’t seem to be any strict threshold for how much food a place must (relatively) sell in order to earn the -s suffix. If that were the case, all fast food vendors and grocery stores should have been near-automatic yeses.

Instead, it appears that -s can be added to a vendor iff the name:

(A) ends in a conceivably human last name,

(B) has a physical storefront (hence the exclusion of Temu, which is a legitimate surname), and

(C) does not already end in -s (so, something like “Burlingtons’s” or “Marshalls’s” would not fly under any circs).

Thus, Panera’s and Joseph A. Bank’s come across as ok, while Costco’s — an abbreviation of “Cost Company” — does not.

Meijer, funnily enough, was called Meijer’s Thrifty Acres just two or three generations ago. So, the possessive ending there may have simply stuck as the store name was shortened.

And interestingly, Aldi (which the respondent accepted as “Aldi’s”) is not a last name — seemingly violating Principle A. Aldi is instead a syllabic abbreviation of the German “Albrecht Diskont.”

However: Albrecht is a last name! I wondered if my dear Michigander could intuit that a surname was buried somewhere in those four letters, or if he felt that Aldi could be an Italian patronymic. Or, maybe I needed to rethink Principle A altogether.

I have no way of knowing for sure, but the respondent then shared something extremely neat.

The -s ending, he said, communicates something about a legit, knowable person anchoring a business. Whether that someone is real or imagined, his mental grammar insists: there is an agent here.

To me, it also seemed that the -s suffix could signal something about familiarity and recurring social relationships, similar to the rapport expressed through going to “the doctor’s” or “the dentist’s.” And I’d say that a social relationship presupposes agency.

To be as clear as Lake Lansing: I obviously can’t draw conclusions about an entire dialect from one speaker’s intuitions — much less make causal claims about cultural psychology. I am far from an apologist for Whorfianism. As John McWhorter1 argues with typical brilliance in *the* book that got me interested in linguistics: language so often reflects, rather than dictates, thought.

In either case, it is just mind-bending to me how morphological patterns can provide insight into particularities of our mental infrastructure, including how we assign agency, ownership, and even animacy (a topic we’ll save for a later date, as it relates to AI!).

Ultimately, perhaps this wasn’t really a linguistic study so much as an excuse to pester my favorite Michigander with alarmingly specific questions about emporiums (and thankfully, patience is one of his many fine qualities).

But somewhere between the “Trader Joe’s’s” veto and the Burlington’s “ok,” a window allowed me to better understand how his regional dialect might reflect the way that he navigates the world. Which, as it turns out, is a very good way to navigate things.

And to Dr. McWhorter directly: my apologies for the parade of apostrophes in this piece. 39, by my last panicked count. You are absolutely correct that most are unnecessary. But please trust that at least a few earned their keep here — in your words, there was a “genuine possibility of ambiguity.” Without them, I risked mistaking one store belonging to Agent “Kroger” for seven or nine of its kind.