What AI Developers Can Learn From A Chapter In The Empire State Building's History

On repurposed dreams and the ROI of spectacle

I craned my neck up towards the Empire State Building last week, completely overwhelmed by its dizzying height and overall stature.

A Google search was in order. (This was not the first time I tried to flee from the discomfort of physical vertigo into the airy dimension of trivia). And what I found did not disappoint.

The ESB, it turns out, is so enormous that it has a ZIP code unto itself. 20,000 people work each day inside this vertical village.

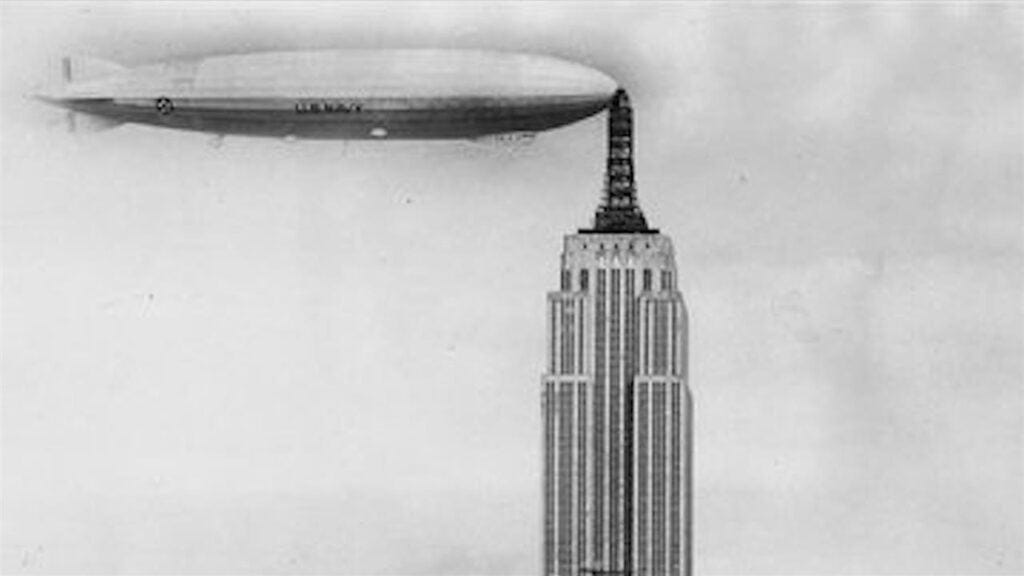

But one historical footnote stuck out from the rest, and contains what I think is an unexpectedly resonant lesson for AI developers. The Empire State Building was originally intended as a docking station for dirigible airships.

Mooring in Midair

Yes, Al Smith (presidential-candidate-turned-overseer of the ESB’s construction) announced in 1929 that the building would increase in height by 200 feet to accommodate the mooring of dirigibles. This was perhaps a thinly-veiled attempt to clinch the title of world’s tallest building — in true keeping with NY state’s motto, Excelsior.

I kid you not. The vision was for passengers to descend via gangplanks from a gently-bobbing blimp onto a two-and-a-half-foot-wide terrace. And the entire skyborne rendezvous would take place no lower than twelve hundred feet in the air.

To the surprise of no one (except, presumably, Al Smith), experts were critical. Dr. Hugo Eckener — creator and commander of the famed Graf Zeppelin — warned that dirigible landings call for serious coordination, lots of rope, and numerous boots on the ground.

And it seems that Eckener was onto something. In 1931, when a privately-owned airship did dock atop the Empire State Building’s spire (for 3 harrowing minutes!), it battled 40-mph winds that the New York Times called “treacherous.”

Ultimately, the dirigible-docking plan fell through. In fact, two years after the original airship mooring proposal, the ESB’s spire was converted into a broadcast transmitter tower, due to the “infeasibility of mooring an airship, for any length of time, to a very tall mast in the middle of an urban area.”

The Merits of Knowing When to Stop, in Two Examples

So, what can this historical ESB tangent teach AI developers?

We need to have the humility to abandon certain ideas or repurpose inventions — especially when the shimmer of spectacle seduces us into building things that look good in a skyline (or a headline), but fail to serve those standing on the ground.

This isn’t to say that, as far as innovation goes, every misstep is for naught. My characteristically kind-hearted mother frequently told me growing up that “there is no such thing as wasted work” (most often in response to my own college, grant, award, and job rejections. Bless her soul).

I agree with the sentiment as it relates to individual lives, just as I do Kurt Vonnegut’s point that writing is a reward in and of itself. Effort decoupled from outcome can enrich and dignify the way we spend our time.

But when the effort in question is that of billion-dollar enterprises and civilization-changing technologies, the equation shifts. If a product’s returns on human wellbeing are minimal, certain projects may simply not be worth the trouble. Sometimes we are better served changing course altogether.

Here are two such examples that I appreciate — where technological advances were paused or diverted:

(1) In 2022, Meta’s Galactica was billed as a revolutionary language model trained on 48 million scientific papers. Galactica was allegedly capable of summarizing and reasoning through huge amounts of scientific data.

But the LLM spouted some hallucinations (before the term was widely adopted). And by that, I mean responses to questions about vaccines that literally read, “to explain, the answer is no… the answer is yes.”

Publicly released two weeks before ChatGPT, Galactica was shut down after two mere days. According to Joelle Pineau, then-Vice President of AI research at Meta, the company closed the demo “to make sure that people were not misled into using it.”

And as far as redirection goes, Galactica taught the company “a lot of good lessons,” including in refining its next language model generation, Llama (which quickly became an international sensation! The effort of building Galactica seemed to become refocused, not wasted).

(2) Though not spearheaded by one company in the way that the ESB or Galactica were, Virtual Reality (VR) was once touted as the next frontier in entertainment.

In fact, early VR prototypes — like Morton Heilig’s Sensorama of the 1960s — aimed to immerse viewers in a so-called “Experience Theater” of film. Even earlier on, precursors like the View-Master stereoscope delivered 3D-like glimpses into television scenes:

But VR systems of today have found some of their most powerful applications elsewhere. The University of Washington’s SnowWorld, for example, is a program developed not for leisure, but to help burn survivors manage pain during wound care.

Though entertainment-based VR systems may be perfectly innocuous and less obviously perilous than disembarking an airship 1200 feet over 34th street, SnowWorld feels like a far more constructive, healing application of the VR medium than headset-based space shooters and tableaus of the Wild West. It serves as a reminder that some technological visions need not be abandoned — just rerouted toward more human ends.

Hype Vs. Humility in Upcoming Years

Now, let’s return to (what was for four decades) the world’s tallest building.

We’re left asking: what use are bragging rights to a superlative (be it about height, speed, or scale) if the technology behind it is impractical to implement… or ill-suited to actually helping human beings?

The ESB dirigible-docking dream, as we saw, never took root. But the ESB’s spire now broadcasts more than a dozen FM radio stations to millions of listeners in the tri-state area — a fruitful repurposing of the same mast that Dr. Eckener once side-eyed.

With AI systems, we should be just as prepared to reassess and redirect. This is an urgent call, and now more so than ever. Today’s models are increasingly capable of strategic deceit. DeepMind’s Demis Hassabis reminded us earlier this year that deception is a “core feature you really don’t want in a system,” as it invalidates all other safety tests (again, a longer post for a different day).

The parallels to Babel, Icarus, and Macbeth are difficult to ignore — timeless tales about ambition and hubris begetting cosmic disaster. If nothing else, we owe it to one another to introspect more deeply and engage in conversations about what we're making, why it matters, and who it serves.

After Babel, humans were separated through language. And in the age of AI, we may well become oversaturated by it. So, it’s time we select our words wisely and begin trading each “look what I built!” for a “who can this help?”

Thank you for being a champion of wisdom!

Regarding closing paragraph, "After Babel, humans were separated through language. And in the age of AI, we may well become oversaturated by it." It may be more so that in place of language, we will be separated by identity. Although it is simple or obvious, it is necessary to remember that Babel brought people together into a single community, hence language was the best method to tear it down, where AI will drive people into becoming toxically individual.