Art “can only be expressed very badly in abstract terms because the subject is already itself an abstract thought. But surely you will understand what I’m saying if you consider how a whole enormous landscape passes through the narrow opening of the eye.”

AI-generated art is breaking hearts, and making bank.

Last month, a Stanford study analyzed over 3.2 million images to understand the effect of AI-generated material on human-made content.

Its findings? After AI-generated images entered the consumer market in December 2022, overall image sales increased — while sales of human-made images plummeted.

Perhaps more strikingly, consumers showed a preference for AI-generated images over those made by humans, which is nothing short of “unwelcome news” for human artists, illustrators, and photographers alike.

Is AI-generated art revolutionary? Of course. But more fundamentally, is it a contradiction in terms?

That is, is AI-generated art even art?

Today, I propose a way to answer that question: by applying what I’ll call the Tolstoy Test. (And apologies in advance — as if tech discourse really needed another T-initial diagnostic).

Does This Count as Art?! The Tolstoy Test

Tolstoy left the world not only with 165,000 manuscript sheets, but also with a standard.

Art, in his words, is “a human activity [whereby] one man consciously, by means of certain external signs, hands on to others feelings he has lived through, and that other people are infected by these feelings and also experience them.”

So, by this definition, at least two conditions must be met for something to qualify as art:

An experience lived

An audience emotionally infected by an encoding of that lived experience.

But what counts as "lived” feelings? I don’t (personally) think that Tolstoy’s notion is limited to literal, autobiographical memory. Sci-fi authors, for instance, needn’t time-travel to experience the existential tensions and questions that their world-building brings to life.

Further, MC Escher’s lithograph of a physically impossible staircase didn’t arise from direct observation of a world without gravity, but from his own internal grappling with concepts like chaos and illusion.

In this sense, feelings may include imaginative projections, so long as they are phenomenally rooted in the experiences of a conscious subject’s mind.

So with that in place, let’s now put a famous image to the Tolstoy Test.

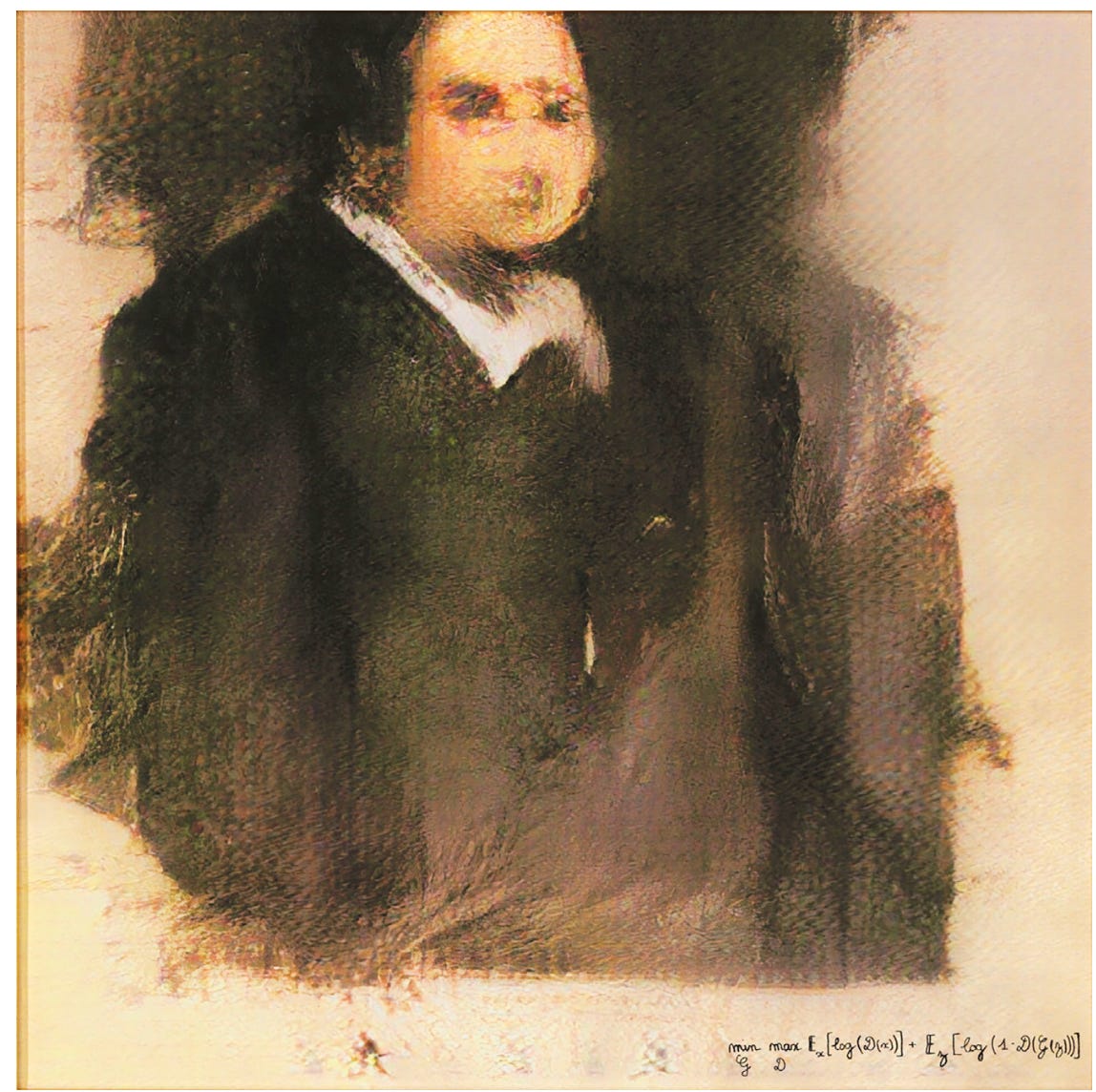

A Curious Inversion: Case Study of the GAN

In 2018, an image generated by a machine learning architecture called a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) sold for over $432,000 at a Christie’s auction.

Our Tolstoy Test hinges on the question of whether a given AI system has the capacity for phenomenal consciousness: personal, subjective experiences.

So, we must ask: was the neural network communicating some lived experience by producing Edmond de Belamy? Allow me to momentarily channel Simon Cowell with a resounding “no.” There is a strong argument that (at least to date) the GAN had no experience to transmit.

To be clear, I think that phenomenal consciousness is substrate-independent — it doesn’t necessarily have to arise from biological matter. I'm intrigued by the functionalist analogy that consciousness is like chess: what its pieces are made of doesn’t matter. So, I’m not suggesting that the GAN will never be conscious — simply that it isn’t, to our current understanding.

However, to complicate Tolstoy Test matters, the GAN was trained on human art. So, perhaps one could argue that although the GAN itself lacked consciousness, it did indirectly communicate the lived (human) experiences of the Renaissance masters in its training data.

Yet if we follow that chain of thought, trouble looks us in the eyes (perhaps from directly below Edmond’s bushy brows).

Even if this model wasn’t trained on images made by conscious entities, the neural net architecture was built by humans. Does that mean that everything a GAN produces indirectly transmits a conscious experience? By that logic, the output of any human-made system qualifies as art — which dilutes the category beyond recognition.

So, if you sincerely believe that your dishwasher's cycle-complete jingle deserves a gallery debut, I honestly respect your principled enthusiasm (as my wonderful father would say: “de gustibus”).

Yet according to Tolstoy, art unambiguously requires “conscious” creation. So unless you’re prepared to argue that the GAN felt anything at all, Edmond de Belamy fails to meet our Tolstoy Test’s first condition: an experience lived.

By Contrast: Why A (Human-Made) Sign for Pork Buns Is Art

Now, onto a very different kind of visual stimulus: restaurant advertisements.

Picture a human designer who’s physically hungry. She needs money to buy groceries, pay rent, and feed her family — and this interior experience directly motivates her to assemble a delightful poster (which, to the best of my knowledge, was human-made):

A stranger passes by, sees the ad, and suddenly feels hungry. Or perhaps he already was, but in either case, his desire intensifies. He walks inside and orders a delicious plate of baozi.

What just happened?

The contagion of experience. Certain “feelings” that the designer “lived through” (hunger, perhaps, but also yearning more broadly) were transmitted in some capacity through the visual medium to another person.

Which, by both conditions of Tolstoy’s definition, qualifies as art.

Beyond the Tolstoy Test

My conclusion: AI-generated art doesn’t qualify as art (at least, not yet). But human-made advertisements? Yes, they just may.

Given the inversion we’ve landed upon, it’s perfectly reasonable to ask: will there be any demand for human art in the future?

I guess: yes.

In my view, there is a basically unending human appetite to connect with the phenomenal consciousness that animates pictures, media, and writing; to identify the someone who felt something first.

That craving, I suspect, may be at least in part why Chen Qiufan predicts that celebritydom and cults of personality will robustly persist into the age of AI. The public still wants to commune with a consciousness.

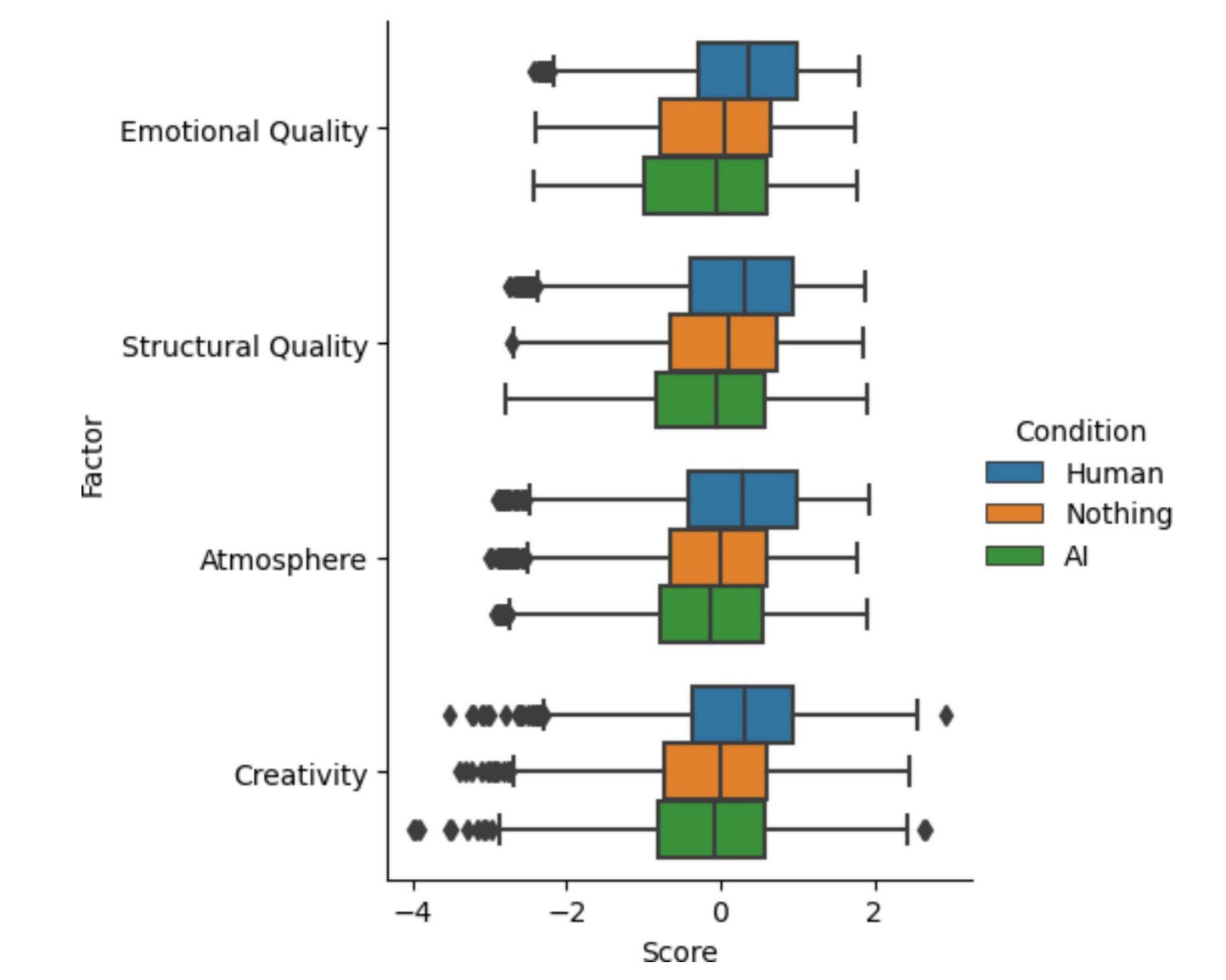

Perhaps that same impulse can also help explain why humans rate AI-generated poetry lower when they are told it is AI-generated (even though, when the same poems are anonymized, participants actually rate AI-generated poems higher than human-written ones):

But if we revisit Tolstoy’s formulation about “feelings” and “external signs,” our line of inquiry may need to be re-examined altogether.

Personally, I feel that this whole exercise illuminates the inherent fragility of categories as well as the concocted division between “art” and other disciplines. The ancient Greek concept of techne encompassed mathematics, music, medicine, and shoemaking. I stand by my reference belief that the ultimate reality constitutes one unit; the human brain, ever eager to sort and segment as a means of processing, invents boundaries where none intrinsically exist.

Thus, as I see things, the real task ahead does not lie in policing the shoddy (if not entirely imaginary) borders of “art.”

Rather, it involves understanding how art and other forms of expression can serve our drive to find union with others — and with the rest of the extensional world. The most fruitful questions we can ask about AI-generated art don’t begin with “is” or “what,” but with “how” and “why.”

What an enjoyable meditation!